I have a really good job for an ER doctor.

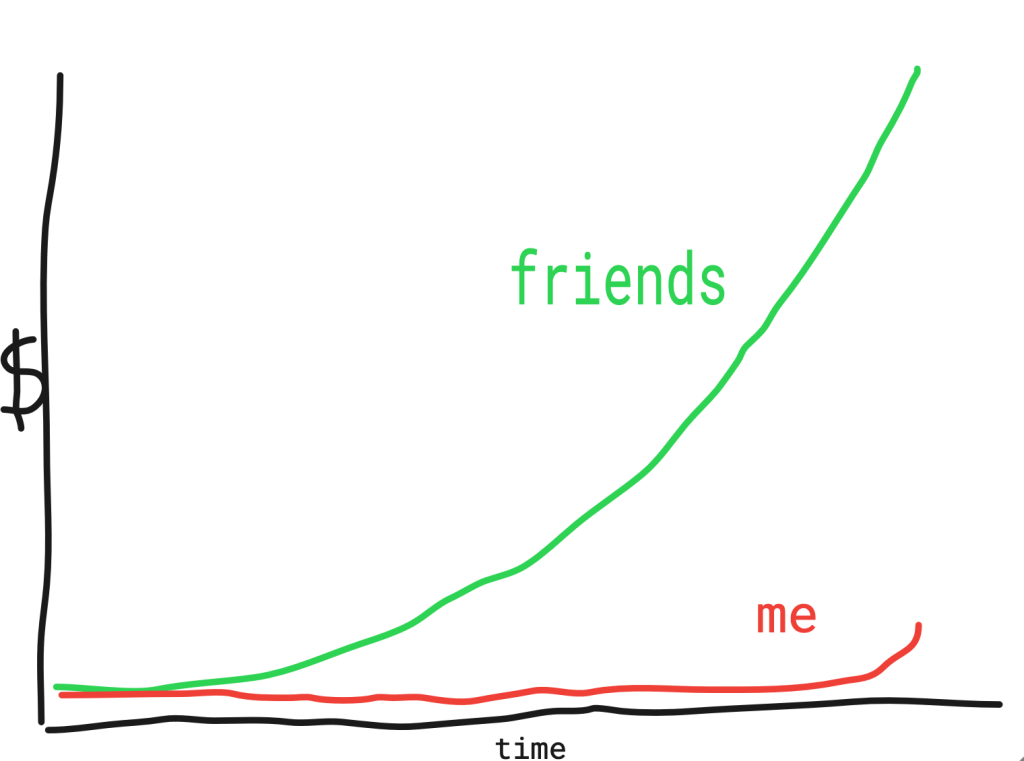

I think it’s important to state that up front, because after eight years of post-medical school training (four residency, two toxicology fellowship) and twelve years of delayed income growth, I’m finally a grown-up making grown-up doctor money. Here is a chart I made showing how far behind my friends I am!

My emergency department administration is remarkably supportive and helped me launch a toxicology consultation service. So I split my time between working ER shifts and doing tox consults. It’s great, especially insofar as it means I work fewer ER shifts.

Launching a brand-new consultation service – especially one where half the administrative people that need to be involved have no idea what “toxicology” is, unlike, say, cardiology – took about four months of meetings, pleadings, emails, calls, and begging. I would estimate that about 80% of the hospital staff are still unaware of the service’s existence or when they should call me.

Now that I’ve been up and running for almost six months, I’ve been trying to gather some data on how I’m doing. You will be thoroughly shocked to hear that no one appears to have any idea.

When I write a note, which represents my proof of work to the billers/insurance company/administrative head of cabbage that runs medical care, I have to assign a “charge” to that note. That means I have to decide how much money* to charge the insurance company, depending on how complicated the patient is, how sick they are, how complex their care is, etc.

*no one actually knows how much money. This is foreshadowing.

There are a bunch of different charge “levels,” numbered from 1 to 5, with 5 representing the highest level of complexity. Tox patients are almost always a level 5.

Of course, what I actually select is not a box called “Level 5” or “Most Complex Patient.” That would be too simple. Instead, the Level 5 charge is called “PR EMER/URGENT SEV/HI COMPLEX.” A Level 4 charge is labeled “PR EMER/HI SEV/HI COMPLEX.”

See the difference?

Wait. I might have that backwards.

Anyway. After I select the charge in our electronic medical record, I’m done.

As a brief aside: in medical school we had a vascular surgeon (let’s call him, uh, Dr. Vain) who was an absolute MASTER of pimping. When you’d scrub in to one of those cases, he would start cutting and then say, “So, Nate, I’m a red blood cell in the heart. Where do I go?” He would proceed to spend the subsequent hours mercilessly interrogating you on where the second branch of the external carotid artery goes, or where the blood cell goes after passing into the posterior tibial artery on its way through the I-5 / 101 freeway exchange during the Friday afternoon rush hour. It was brutal.

After I submit my note and charge, where does it go?

To answer that, I spent a few hours on Zoom and over email with some of the billing people. I left all of those interactions far more confused than an unprepared med student in the OR with Dr. Vain.

Here was my question to the group. I think you, normal reader in or out of healthcare, will all agree this is a normal, not-insane question that should have a straightforward answer.

“How much money have I generated in toxicology consultations since we started?”

That’s it. That was the whole question!

The best answer I received: “No one knows.” No one has any idea how much money my consults generate, either on a one-by-one basis or in aggregate. The only explanation I can come up with for why no one knows is that the billing and coding people are aliens from another galaxy who speak an entirely different language than doctors. They communicate in five-digit number sequences. I believe their physical forms most closely resemble Clippy, floating in a hazy atmosphere of Excel !VALUE symbols.

Allow me to explain.

When I finish a “Level 5” chart, this request lands in the inbox of Alien Coder #1. Clippy must first decide if this is an “inpatient” chart or an “outpatient” chart. This should be straightforward, considering almost all of my consults are from admitted patients physically in the hospital (…inpatients) or from patients in the emergency department. I should note that the emergency department is physically located INSIDE the hospital. It is, in fact, the basement floor of this particular hospital. When tests are run on these patients, they are performed at the INPATIENT laboratory, again located INSIDE the hospital.

Emergency department patients are considered outpatients for billing purposes which MAKES ABSOLUTELY NO FUCKING SENSE but whatever.

Clippy’s decision is, however, not that straightforward. What if the patient is admitted (and thus becomes an actual inpatient) between the time I am consulted and when I finish my note? What if the patient’s care is transferred over to a hospitalist, making them an inpatient, but they are physically still located in the emergency department waiting for a bed? WHO CODES THIS NOW?

When this existential question came up, there was a heated debate between Clippy and Alien Coder #2, whom I shall call Stephanie, over whether we should be billing 99285 or 99205, with or without the GT modifier.

What is 99285? What is 99205? What is happening?? THE CODERS DON’T EVEN UNDERSTAND EACH OTHER’S NUMBER-LANGUAGE.

These five digit numbers are called CPT codes, for the highly descriptive acronym “Current Procedural Terminology.” I am not making this up. (These codes were established by the American Medical Association, a ginormously bloated ogre of a professional society, so top-heavy that even trying to figure out who runs it took twenty minutes of my time before I gave up. See for yourself.)

Anyway. This all matters because the inpatient coder (Clippy) and the outpatient coder (Stephanie) have entirely separate workflows that somehow don’t overlap at all. Stephanie doesn’t even understand Clippy’s job, and vice versa. They operate in parallel Kafka prisons that do not touch and generally they are unaware of the others’ existence (except when forced onto Zoom calls by some pathetic physician.)

After the coders decide, somehow, whether to bill 99284 or 99285 or 99203 or bleep bloop bloop, they submit it to the patient’s insurance company. I think.

And then, after THEIR Clippys and Stephanies decide if a) the billing location and code is correct; b) the chart supports that level of service; c) the patient is up to date on their premiums, hasn’t met their lifetime go fuck yourself limit, and it’s a Wednesday during a waning gibbous moon — then, and only then, they pay like $90 to the hospital.

Of course, that $90 could be anywhere from $3.50 to $99 depending on whether we are talking about Medicaid insurance ($0.50) or BlueLife MegaStar Plus Gilded Butthole insurance ($99).

This process can take anywhere from 90 days to forever.

It is insane. This process is so incredibly insane that most people don’t even realize it exists. Those that are aware of its existence have no idea how to operate it or manipulate its outcome. It is bananas, and always reminds me it’s a good time for this chart:

It’s almost like the entirety of our outrageously priced healthcare system costs are driven by the intrinsic psychosis of our complicated insurance world. If this system made even a tiny bit of sense, none of these people would need to exist! Clippy and Stephanie are nice and knowledgeable people… that hold jobs that simply should not exist. And I wouldn’t have to check PR EMER/URGENT SEV/HI COMPLEX and then have no idea what’s going on for the next six months.

Otis agrees.

oh but you forgot about the ridiculous world of observation where you literally are admitted to the hospital, but your insurance pays as if you’re outpatient 🙄

I know what this means, but I also don’t know what this means. Which is the whole crazy point!

“It’s almost like the entirety of our outrageously priced healthcare system costs are driven by the intrinsic psychosis of our complicated insurance world.” As a European … yes.

funny

Pingback: A Highly Interchangeable Modular Part | crashing resident